I arrived at Porsche Center Denver feeling disoriented; my flight in was plagued with supercells and turbulence, swinging us so far in avoidance of the worst that there was a brief moment where Salt Lake City was our alternative landing spot. Planes are marvels in their own right, but unlike ground transportation and regardless of the luxury that you may be able to afford, there’s zero sense of freedom. You spend hours, bound to your allocated seat, not because you want to be there, but as a means to an end. So there I sat, admittedly quite anxious, but safe in the knowledge that there was something better waiting on the other side. A car as vibrant as the landscape that lay ahead of it: Guards Red, Aurum wheels, and as powerful as the supercells we dodged only a few hours earlier.

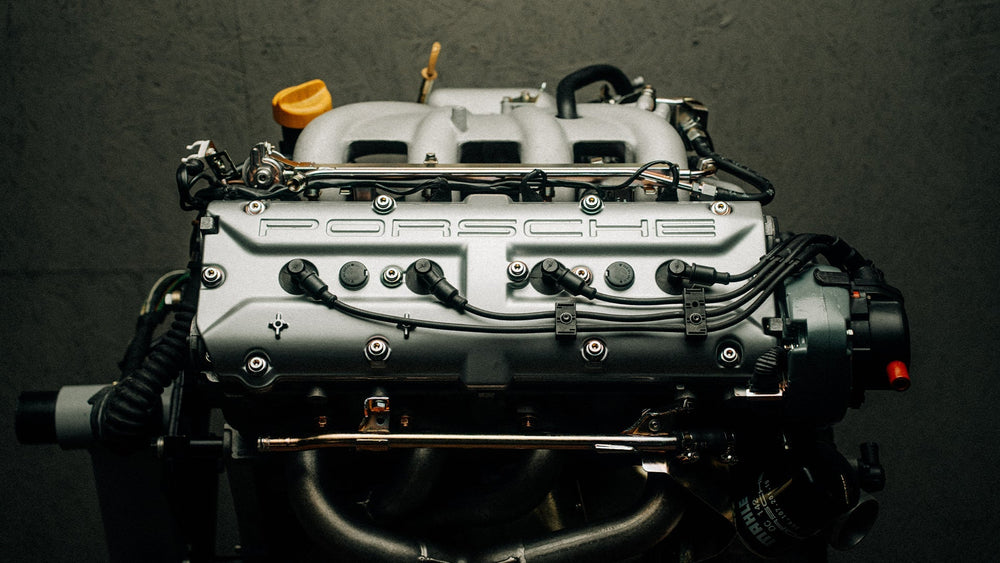

The 911 Turbo S comes with a serious reputation; a continent crusher that can hold its own against almost anything and the pinnacle of Porsche’s 60+ year commitment to refining the 911 model. In my hazy, sleep-deprived state, it was a sight for sore eyes. Real connections, the type that called out to me, aren’t made in the moment – like the 911, they develop over time. Thankfully, that was a resource we had in plentiful supply, and thousands of miles lay ahead of us.

Denver was the starting point for a free-flowing route that would ultimately come to a close in San Francisco, with some key stops ahead of us that would give both myself and the car an opportunity to soak in the best of the American west. A true American road trip, the kind dreamed about by those of us on the other side of the pond, a vast space of land unfolding in front of you. We have more than our fair share of extraordinary landscapes, but nothing like this. Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and California each contain an almost unimaginable level of diversity. Microclimates, Martian plateaus, searing deserts, snow-capped peaks, vast forests and sweeping beaches, all for the taking if you have the gas money and a bit of time.

Over a decade ago, when I found myself briefly living in the US, I spent some time on many of the same roads. As a teenager, in the earliest days of what has turned into a career, a friend and I found ourselves returning to Los Angeles from Pikes Peak via the scenic route. The I-70 was simply too much of a drag after a weekend spent in the clouds, so we pulled together the little gas money we had. In those hours along the roads there was a galvanising moment, where I knew the only thing I wanted to do was spend time around cars.

With the feeling of that memory in mind and keys firmly in hand, I went on my way. The frisson at start-up was a strong indicator that we were in for a good run, and I knew immediately where to go first.

Just a stone’s throw outside Denver’s sprawl is Red Rocks, a place that would feel like a preserved slice of the Jurassic if not for the amphitheatre now hosted in the middle of it. It’s one of the most impressive venues on earth, and it’s hosted an exhaustive list of names. Winding around the bowl are a series of small roads, threading through a sandstone almost as scarlet as the car.

Beyond the extraordinary beauty, it was an ideal spot to get to grips with the Turbo S before the route stretched out across state lines. Eventually the plains to the east became a distant memory as we climbed into the foothills of the Rockies, each altitude signpost notching upwards. The thin air did very little to dampen the power underfoot – after all, the Turbo S obliterated the production car record in the 2022 Race to the Clouds at Pikes Peak. Heading between the legendary hillclimb mountain and Mt. Blue Sky, we hugged the southern edge of the range, eventually looping northwards through the ski towns of Vail towards the state line.

Our single foray on the I-70 was also its most scenic span, swooping through the enormous cliffs around Grizzly Creek, carved out by the Colorado River. Then the mountains gave way to descending plateaus, and Utah lay ahead, the sun setting into the desert haze dividing horizon and empty land. We started the day in civilisation, but hundreds of miles later the only thing near was the eerie silhouettes of Cisco – a town which barely made it into the 20th Century long enough to be afforded its own ZIP code. On my first journey over a decade ago we made the run from Colorado all the way to the Grand Canyon in a single day: this time our first overnight stop was Moab, and in the stretch between here and bed, there was just enough time to stop.

An ethereal soundscape provided by the coyotes howling in the distance, and the pinging of the Turbo S’s exhausts cooling down as the searing heat dissipated, the Milky Way glittered in a night sky dark enough to make the density of Europe feel like a galaxy away.

Type 7’s Editor Nat Twiss journeys far into the American West to reconnect with his roots in car culture.

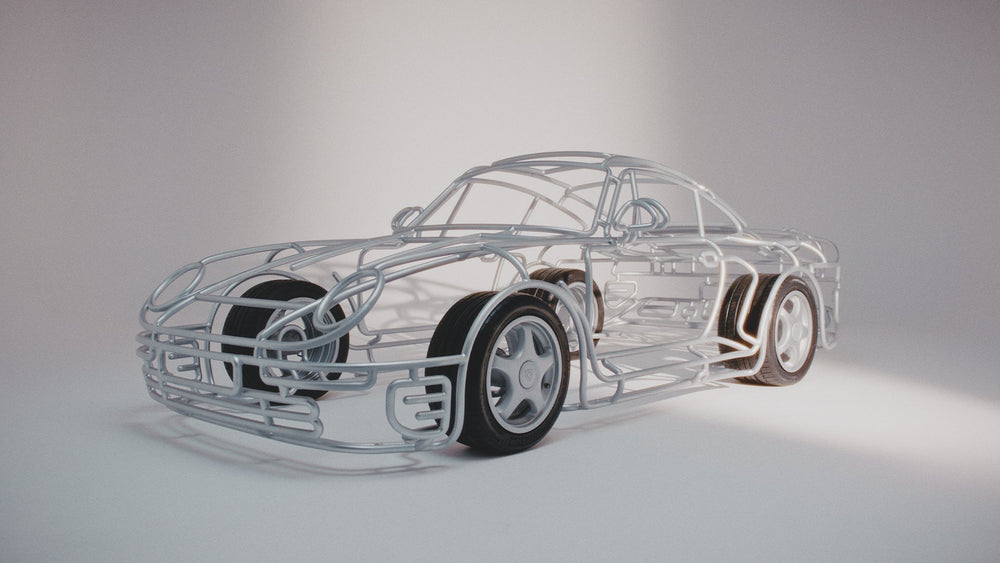

There’s a moment that gets infinitely rarer the more time you spend around cars where everything truly clicks. Sportspeople call it a flow state, some might compare it to a form of meditation. Cars are ultimately objects – albeit extremely impressive ones, a fusion of a thousand minds aiming to create the best ‘thing’ possible, combining centuries of design and engineering into a package offering a freedom that little else can – but until a human interacts with it, they don’t have a real purpose.

At least, that’s what those of us who have a passion for cars tell ourselves, but recently it’s a purpose that, I’m ashamed to admit, has been increasingly elusive - especially given that in recent years I’ve served as the Editor of Type 7, a platform designed to help explore and promote that purpose in a world where people are becoming less and less engaged by what they drive. I was becoming worried that I was falling victim to it too. Maybe I needed a reminder. It’s precisely why I found myself on a plane over the Atlantic, en route to Denver, to see if there was still anything left to be found.