“Brian did the film because of the generative doc idea” Hustwit says of the pitching process, continuing “We had a basic version of the platform early on and we showed Brian a demo that used the raw material from Rams as a proof-of-concept before he agreed to do it. When we showed it to him, he said something like ‘I feel like this is going to unlock something that I've been wanting to do for a long time.’ So It wasn't because he was dying to have a documentary film made about him, he wanted to be part of this experiment in filmmaking and he’s been using generative software in his music making for 30 years now. He's always experimenting with technology and very curious about it. The price he had to pay was that the film had to be about him.”

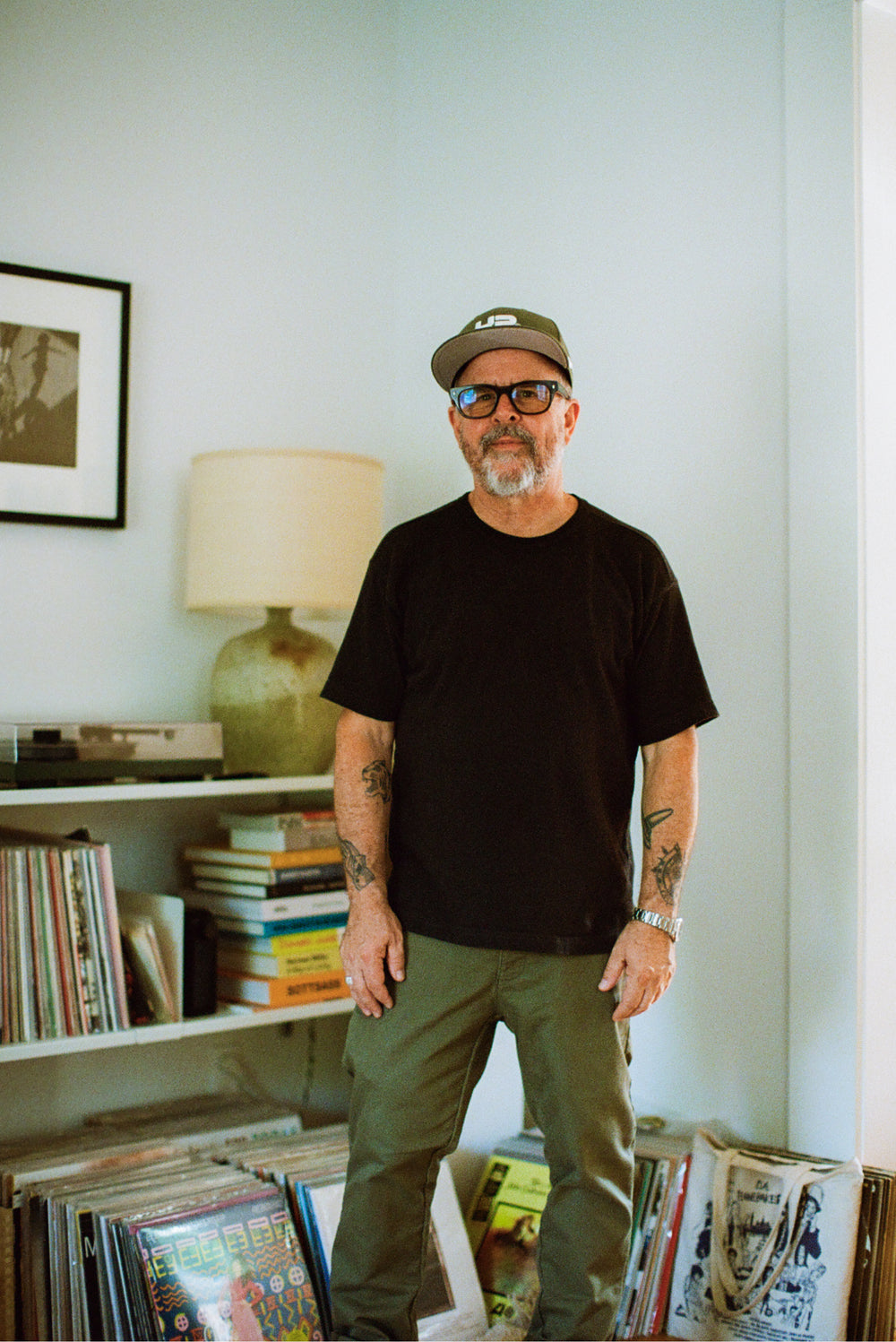

From his innovative filmmaking to his 911 build, Hustwit has always thrived on working with other creatives. For Hustwit, every pursuit and collaboration is a learning experience and he says of making Eno that “The bigger lessons I learned about creativity from Brian are the macro ones about his career and how he's progressed; how none of it was planned and how he was just going with his feelings about things and moving forward. Brian’s really stayed true to his own artistic principles and his own sense of creativity, and I think that that's one of the reasons why he's still so engaged and so curious. So many creatives lose that curiosity over the years. It’s amazing to see that curiosity in action and to see him still working every day.”

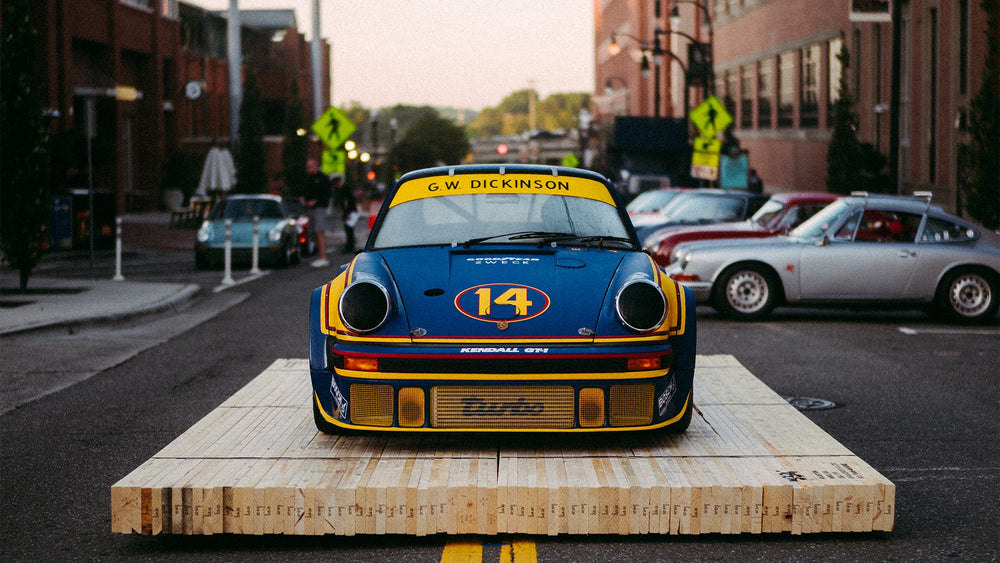

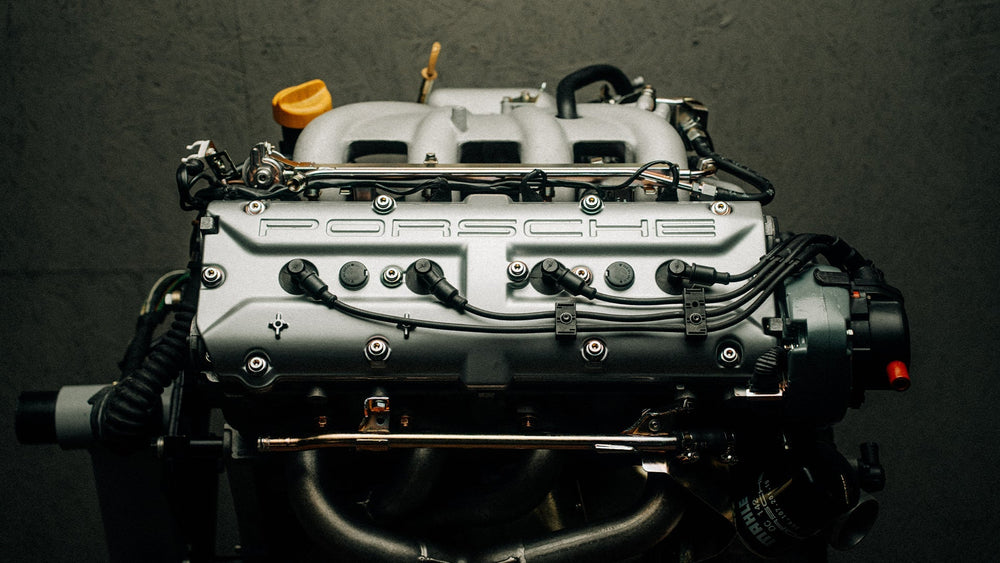

Every version of Eno makes one thing abundantly clear: There is no limit to how and where one can apply an artist’s touch if they take a holistic approach and stay curious. A prime example of that in practice is Hustwit’s impressively unique 911 build. Known as the Kronberg 911, the car was dreamt up and built in collaboration with Richard Gonçalves of ROCS Motorsports in New Jersey and is unlike any other vintage 911 you’ve seen before.

Generative Creativity

Author: David Von Bader

Photographer: Hagop Kalaidjian

Filmmaker and Kronberg 911 Owner Gary Hustwit’s Perpetual Creative Paths

Since pictures first moved, films have always been created and experienced in the form of a fixed edit. Save for a laborious director’s cut or alternate edit release, pretty much every film ever made has been presented with its original story essentially intact every time it’s been screened. So to consider fundamentally changing the way a medium as established as film is crafted and experienced takes more than just a unique vision – it takes guts. However, for filmmaker, lifelong student of creativity, and air-cooled Porsche 911 devotee Gary Hustwit, finding a way to free film from the shackles of the fixed edit was just another step off-the-beaten path in a career that’s been defined by a consistent drive to take things elsewhere.From his early days as a DIY publisher in Southern California’s punk-rock scene to being the first documentarian to bring the intrigue of industrial design to the masses with his film Objectified, to his high concept Braun-themed 911 art car, Hustwit has always had an uncanny ability to both recognize the thing that was missing from the moment and then bring it into being. He’s something of a bloodhound for the unexpected. His latest work, Eno, does that once again, but it also kicks open the door to an entirely new category of film.

Eno delves into the life, creative processes, and philosophies of maverick music producer, Godfather of ambient music, and paradigm-shifting creative Brian Eno. It’s also the world’s first generative film, meaning every screening of it presents a wholly distinct edit that’s generated as the film is shown. The overlap from screening-to-screening of what footage is shown, how that footage is sequenced, and the way the film’s artful, techno-psychedelic visual segues are applied between scenes is impossibly slim – to the point that 52 quintillion versions of the film could be created before one is repeated.

“Right around the time that Brian [Eno] had done the soundtrack for my film Rams, I started thinking about films that could evolve,” Hustwit explains of Eno’s origins. “You pour so much into a film, and then it exists and you move onto your next project. I wondered how I could make filmmaking more performative like music, and why films had to be this fixed, static thing? Why can't we make films that are performed? We’ve been so dazzled by the motion picture that we never really thought about the constraints of linear storytelling. Generations of audiences and filmmakers have just accepted that constraint as part of the medium for 130 years. There have been incredible innovations in filmmaking in that time, but the basic form has never really changed. Now that we have the technology to do it, I thought ‘Why not try it? Why not experiment?’”

While one might assume the filmmaker responsible for the world’s first generative documentary is a serious technophile, Hustwit – who loves incorporating analog experiences like his air-cooled 911 into his day-to-day – describes his relationship with technology as one of necessity, saying “I’ve always been excited about technology and the possibilities of it, and it’s been an important thread throughout everything I've done, but it’s more about imagining things that don't exist and then having to invent the technology to make them. It’s a means to an end for me. For Eno, it wasn't that I wanted to play with generative technology, it was that I wanted to make a film that was different every time I showed it. The tech is a byproduct of chasing the capability.”

Eno isn’t AI-powered in the contemporary sense, but it did require the creation of bespoke software to build its generative cuts. Named “Brain One” (a cheeky anagram for Brian Eno), the software was created by Hustwit’s collaborator, digital artist and programmer Brendan Dawes, and it pulls from a collection of over 500 hours of painstakingly edited archival footage that spans the length of Eno’s career, as well as over 50 hours of new interview footage that Hustwit conducted with Eno – who has famously refused interviews for many years. Hustwit also collaborated with Teenage Engineering on the creation of a custom hardware incarnation of Brain One called B-1, a slick, minimalist console that brings the software into the tactile world with an aesthetic nod to the iconic Braun designs of another of Hustwit’s heroes and documentary subjects, Dieter Rams. Hustwit’s use of B-1 to create Eno’s generative edits in theaters adds a whimsical visual layer to the “performance film” experience.

So how does a film – and particularly one categorized as a documentary – work without a strict narrative? Does it become an exercise in texture and ambiance? An abstract experience? Does it feel like reading a William Burroughs cut-up method passage? In the case of Eno (or at least the version I saw at New York City’s Film Forum) the film has those elements, but is also intensely immersive, ethereal, and, remarkably, still provides a deeply informative experience. It was like being strapped to the back of a neuron as it traced the pathways of Eno’s mind and explored ideas on creativity, his past and present works, and his unexpectedly sharp sense of humor. In fact, I left the theater convinced that the generative format was the only appropriate way to bring an audience into Eno’s massive oeuvre (the credits are simply staggering) and philosophies as an artist. It turns out Eno himself felt similarly.